SozPol-Database

The EU Social Policy database provides an overview of the European Union’s Social Policy development from the start of the integration to the end of 2020. It is part of a multi-annual project carried out at the University of Bremen, at Leipzig University and at the Freie Universität Berlin.

The founding treaties of the European Union (EU) considered economic integration to be the key to greater wealth and better living conditions for everyone. Genuine social policy, in turn, should be reserved to the member states. Consequently, member states limited EU social policy competences, and policies unfolded only slowly.

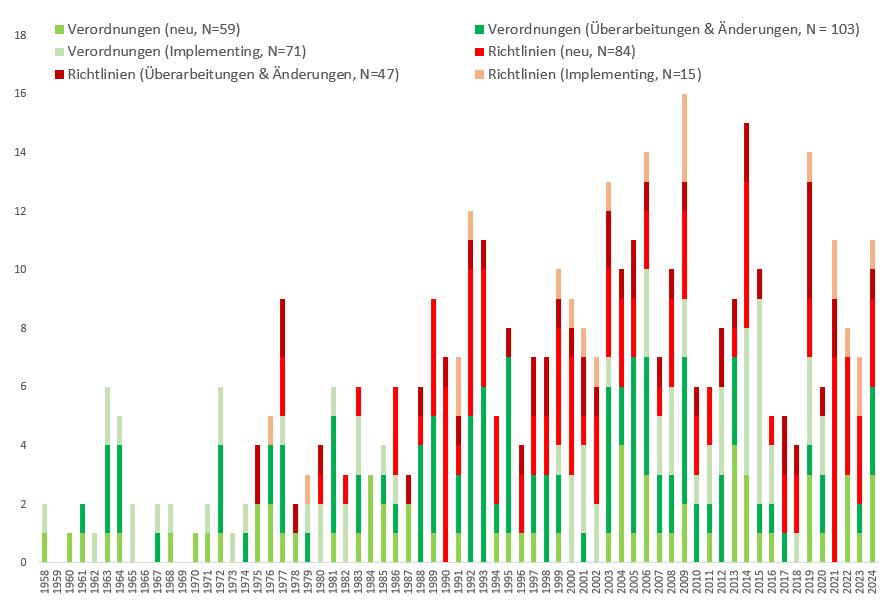

Until the mid-1970s, EU social policy was limited to few instruments. They all were closely linked to the rationale of market integration. Regulation sought coordination of social security systems to support the free circulation of workers or it sought equal pay for male and female workers to avoid a competitive disadvantage for countries that already followed this principle, like France. Spending under the European Social Fund focused on labour market shortages through qualification. In this early phase, EU social policy was limited in the priorities covered, remained largely unnoticed outside the realm of expert circles, and showed little effect for a broader share of the EU population.

This slowly changed when in 1973 the EU Commission proposed a first Social Action Program (SAP) that marked the beginning of more dynamic developments. In line with the aim to establish more visible EU social policies, Commission president Jacques Delors said that ‘one cannot fall in love with the single market’. And when in 1986 the Single European Act created the internal market, social policy supporting the free movement in this market was paralleled by instruments pushing for genuine social goals. A little later the Community Charter of Fundamental Social Rights of Workers was adopted (1989), and the Maastricht Treaty (1992) included a Social Protocol signed by all member states but the UK (who later joined after a change from Tories to Labour government). The Amsterdam Treaty (1997) added an employment title and a new anti-discrimination article. These changes are important as they led to a broadening of priorities and in many areas an easing of decision-making via qualified majority voting. On this basis a minimum floor of labour standards was established, e.g. on working time, European Works Councils, and information and consultation. And, the EU level attracted new actors actively pushing for and shaping EU social policy, such as EU level social partners and a number of social NGOs.

Here is a selection of scientific articles, that make use of the Database:

Graziano, Paolo R. und Miriam Hartlapp. 2019. The End of Social Europe? Understanding EU Social Policy Change. Journal of European Public Policy 26 (10): 1484-1501. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1531911. To the article

Hartlapp, Miriam. 2019. Revisiting patterns in EU regulatory social policy: (still) supporting the market or social goals in their own right? Zeitschrift für Sozialreform 56 (1): 59–81. doi: 10.1515/zsr-2019-0003. To the article

Hartlapp, M. (2020) ’European Union Social Policy: Facing Deepening Economic Integration and Demand for a More Social Europe With Continuity and Cautiousness’. In Blum, S., Kuhlmann, J. and Schubert, K. (eds) Routledge handbook of European welfare systems. (London, New York: Routledge, Taylor et Francis Group). To the article

Hartlapp, Miriam. 2020. Zwei realistische Perspektiven für einen sozialen Binnenmarkt. Edited by Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, DEUTSCHLANDS VORSITZ IM RAT DER EUROPÄISCHEN UNION JULI DEZEMBER 2020 - Begleitband des Bundesministeriums für Arbeit und Soziales. Berlin. To the article