PEU-Database

The PEU database provides an overview of the European Commission’s historical development from the start of the first Hallstein Commission in 1958 to start of the von der Leyen Commission in 2020 (The deadline for the last data collection was 31 May 2020). The database was created as part of the multi-annual project "Position Formation in the EU Commission" (PEU) at the Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB). Since then, the PEU has been continuously updated at the Center for Comparative Politics of Germany and France at the Free University Berlin (FU).

The database offers different perspectives on the Commission:

- An insight into the personal backgrounds of all 428 persons who have been active as Commissioners and Directors-General from 1958 to 2020 (eg. gender, nationality, party affiliation, former positions/ professional background, further career). ("Persons Data")

- Information on the portfolios (responsibility for directorates-general) of Commissioners and Directors-General, their terms of office and corresponding Commission membership. ("Persons positions")

- Data on the administrative structure of the different Commission DGs ("DG Data")

- An overview of changes in the Commission's portfolio names and competences throughout the history of EU integration ("DG Organizational Evolution")

Files for download:

- the PEU database

- the corresponding User manual

- a document with exemplary findings and graphs

Here is a selection of scientific articles that make use of the Database:

- Hartlapp, M., Müller, H. & Tömmel, I. (2021). "Gender Equality and the European Commission". In G. Abels et al. (eds), Routledge Handbook to Gender and EU Politics. Routledge.

-

Ege, Jörn. 2018. “Learning from the Commission Case: The Comparative Study of Management Change in International Public Administrations.” Public Administration.To the article

-

Rauh, C. (2018) ‘An agenda-setter in decline? Legislative activity of the European Commission 1985-2016. Annual Conference of the European Political Science Association (EPSA) 2018, Vienna’. To the article

-

Graziano, P.R. & Hartlapp, M. (2015) ‘La fin de l’Europe sociale ? Évaluation du rôle des changements politiques et organisationnels au sein du système politique de l’Union européenne’, Revue française des affaires sociales (3): 89–114. To the article

-

Hartlapp, M. (2015) ‘Politicization of the European Commission. When, how and with what impact?’, in M.W. Bauer and J. Trondal (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of the European Administrative System, Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 145–60. To the article

-

Hartlapp, M. & Lorenz, Y. (2015) ‘Die Europäische Kommission – ein (partei)politischer Akteur?’, Leviathan (1): 64–87. To the article

-

Hartlapp, M., Metz, J. & Rauh, C. (2014), Which policy for Europe? : Power and conflict inside the European Commission, Oxford: Oxford University Press. To the article

Example

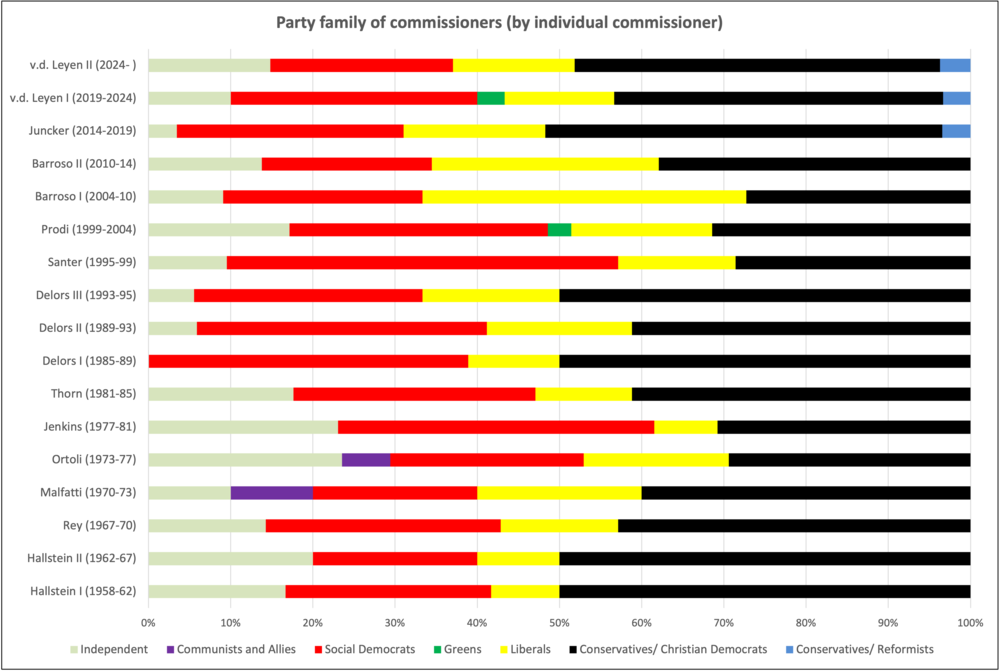

Politicization of the EU has become an important research topic. This graph shows the composition of the particular Commissions regarding their Commissioners’ party affiliation. Assignment is based on which group in the EP the Commissioner’s party in question belonged to at the time (party family groupings build on and further develop Hix and Lord 1997). The graph allows making statements about the relative ideological heterogeneity as well as possible ideological or partisan biases of the various Commissions. This is particularly relevant where we abstain from considering the European Commission a neutral administration. Here, one important insight is that the current College of Commissioners is ideologically more heterogenous than any of its predecessors.